All blog posts ……..Start each work week with the latest issue. Scroll down to subscribe!

Real-world advice for evaluating training

By definition, the goal of training is to change how people behave.

And in most cases, we’re wanting to change behavior because we believed that changed behavior will result in the organization:

- Making more money.

- Losing less money.

- Getting a better reputation (so that the organization can make more money).

- Providing better customer service (so that the organization can retain and attract more customers and…make more money).

- Achieving regulatory compliance (so the organization can stay in business and avoid lawsuits, both of which are necessary to make more money).

So it makes sense that when it comes time to evaluate the effectiveness of our training, we need to think in terms of how we plan to measure changed behavior, including:

- the skills our audiences are able to demonstrate after completing training;

- the tasks they’re able to perform after completing our training; and

- the effects of that changed behavior on the organization’s bottom line.

Unfortunately, that’s often easier said than done.

This article explains why training evaluation in the real world is often difficult or impossible; offers tips for getting as much relevant evaluation data as possible; and suggests how, in the absence of actual data, we can best evaluate training effectiveness.

1. Why getting actual authentic evaluation data is often difficult (or even impossible).

Many organizations face one or more of the following:

- The lack of a cohesive, organization-wide information strategy or architecture. Many organizations use a crazy quilt of computer systems, each of which defines, captures, stores, and reports data differently and each of which is often governed by a different department—all of which typically have competing agendas and varying levels of on-team data expertise. Because these systems typically aren’t well integrated, gathering meaningful, relevant data that crosses departmental lines is time-consuming at best and impossible at worst.

- Challenges associated with tying complex, nuanced behaviors to specific metrics. It’s rare that we’d want to train audiences to perform a simple step (such as push a button) that would have a single effect (such as increase number of sales by one). In the real world, we typically train complex tasks and skills that aren’t easily encapsulated in a single (or even a few) measurements. For example, let’s say we trained our call center in soft skills—greeting customers, asking probing questions, up-selling, and so forth. Up-selling might easily be tracked by comparing historical order revenues before a training vs. after a training. But what metric would we look at to measure our trainees’ newly acquired mastery of asking probing questions?

- Difficulty of isolating training’s contribution to behavior and performance. Behavior is affected by a lot of factors above and beyond trained knowledge and skills: regulations, inter-departmental delays, volume, competing requirements, systems issues, personality clashes, and more. This complexity can make identifying how much of behavior over time is due to training and how much is due to organizational or other environmental factors difficult to gauge.

2. What we often settle for when we can’t get authentic evaluation data.

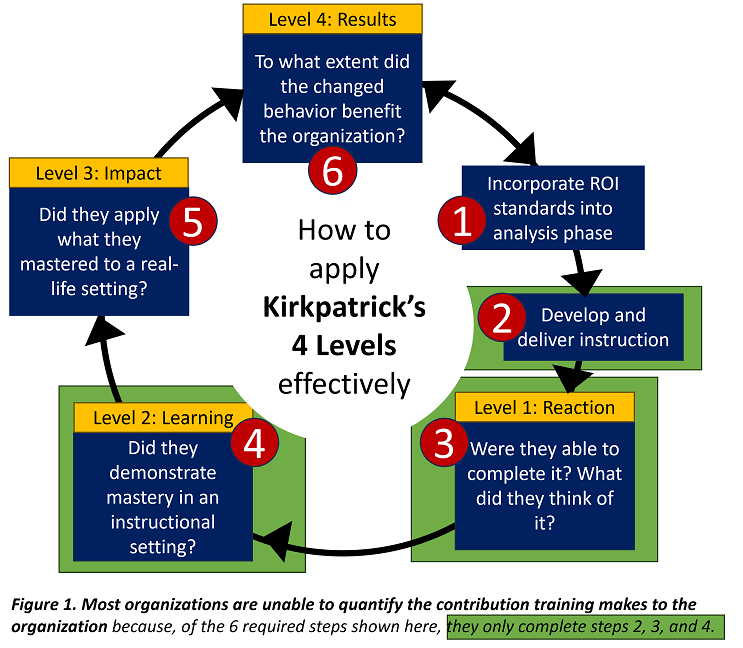

- Kirkpatrick Level 1: Surveys. Many organizations rely on surveys to determine training effectiveness. There are two problems with this approach. First, surveys rely on learner self-reporting, which is notoriously unreliable. Second, even if survey data could be counted on to be accurate, at best surveys are only capable of measuring learner reaction to training—and learner reaction doesn’t correlate to actual behavior. Put simply, surveys are incapable of measuring knowledge, behavior, or skills acquisition. (They are, however, cheap and easy to administer and report, which is why so many organizations use them.)

- Kirkpatrick Level 2: In-training KNOWLEDGE assessments. Some organizations rely on knowledge assessments to determine training effectiveness; but at best, knowledge assessments can only assess learner knowledge—not the willingness or ability of a learner to apply that knowledge in an authentic setting. (And as all of us who have ever made New Year’s resolutions to stop smoking, exercise more, or spend less are likely aware, knowing how to do something emphatically does not mean we’re actually going to do it.) Put simply, knowledge assessments can’t measure behavior.

- Kirkpatrick Level 2: In-training SKILLS assessments. Good instructional designers incorporate skills and performance assessments into their training using story problems and mocked-up scenarios. These are time-consuming to develop and deliver, so most of us incorporate very few—too few to drive true mastery. But even if learners pass our “doing” assessments with flying colors, they’re likely not getting authentic practice because our test scenarios aren’t subject to the same pressures and complexity of a real-life situation. (Earning an A+ on a virtual biology lab, for example, is light years away from dissecting a frog in real life.) Put simply, at best skills assessments measure how well learners perform in an assessment setting, and that measurement is heavily dependent on assessment quality. Skills assessments delivered in training can’t measure how learners behave outside of training, in a real-life setting.

3. What we can do instead.

To evaluate whether or not our training was actually effective in the field (Kirkpatrick Level 3), we can conduct qualitative interviews. We can sit down with the individuals who are most likely to observe the changed behavior we’re trying to measure and ask them questions.

Examples of qualitative interview questions: “Are you seeing more of behavior X now, after the training, than you did prior to the training?” “How much more?” “How often are employees making mistake Y now compared to before the training?” “What behavioral gaps are you still seeing?”)

Qualitative interviews can be a hard sell. Managers these days often demand numbers (even when those numbers don’t make sense) and dashboards (even when those dashboard are cluttered with irrelevant data taken out of context). But in the absence of relevant, accurate hard data (see #1 above), analyzing qualitative data reported in an authentic setting by the people most likely to observe and understand them is the most meaningful evaluation approach.

4. How to streamline evaluation on the next project.

The best way achieve Kirkpatrick Level 4, which is the ability to determine the return on investment (ROI) of a delivered training, is to bake ROI discussions into the very beginning of an instructional project. When we do, we have the framework we need to measure ROI post-delivery.

During the project analysis phase, we need to identify and quantify:

- What business-level improvement we want to achieve.

- What behavioral change we expect will drive that improvement.

- What standard of change is enough to to drive the improvement.

- What that improvement is worth in dollars and cents.

For example, let’s say we’re executives of a retail mail-order company and want to retain more customers. From listening to calls, we suspect that our poor customer service is driving customers away. We decide that:

- Example business-level improvement. We want to retain 10% more customers next fiscal year than we did this fiscal year. We believe this will increase revenues from $250,000 to $400,000 in one year’s time.

- Example behavioral change. We believe improving our call center employees’ soft skills (specifically, greeting customers properly and making small talk) will drive that improvement.

- Example standard of change. We want to see an improvement in greeting and banter in at least 80% of all calls beginning one week post-training (as measured by listening to 50 random calls and applying a predefined rubric).

- Example of quantifying a business-level improvement. We anticipate increased revenues of $150,000 to $300,000 the first year if our standard is met (factoring in the time/$$ required to create the training and to pull call center employees off the phones long enough to complete the training).

Documenting ROI-related goals during the analysis phase of a project is a two-fer: it helps guide project development, and it provides the clear benchmarks we need to evaluate effectiveness post-delivery.

The bottom line (TLDR)

In the real world, many training departments “prove” the effectiveness of training using surveys and in-training assessments—instruments that are easy to administer but incapable of measuring behavioral change in the field. And if management is okay with that approach, perhaps it’s best to let sleeping dogs lie.

When it’s important to quantify the value of training on the business, however, quick-and-easy surveys and grade reports don’t cut it.

Identifying the actual dollars-and-cents impact our training has on an organization requires us to level up—specifically, to achieve Kirkpatrick Levels 3 and 4. And the easiest way to do that is to conduct qualitative interviews with select stakeholders post-training (Level 3) and to bake ROI standards and adherence levels into the project analysis phase for measurement post-training (Level 4).

What’s YOUR take?

Do you have a different point of view? Something to add? A request for an article on a different topic? Please considering sharing your thoughts, questions, or suggestions for future blog articles in the comment box below.

Leave a comment