All blog posts ……..Be sure to scroll down to subscribe!

As social animals, human beings have been engaged in some form of instruction since our appearance on earth.

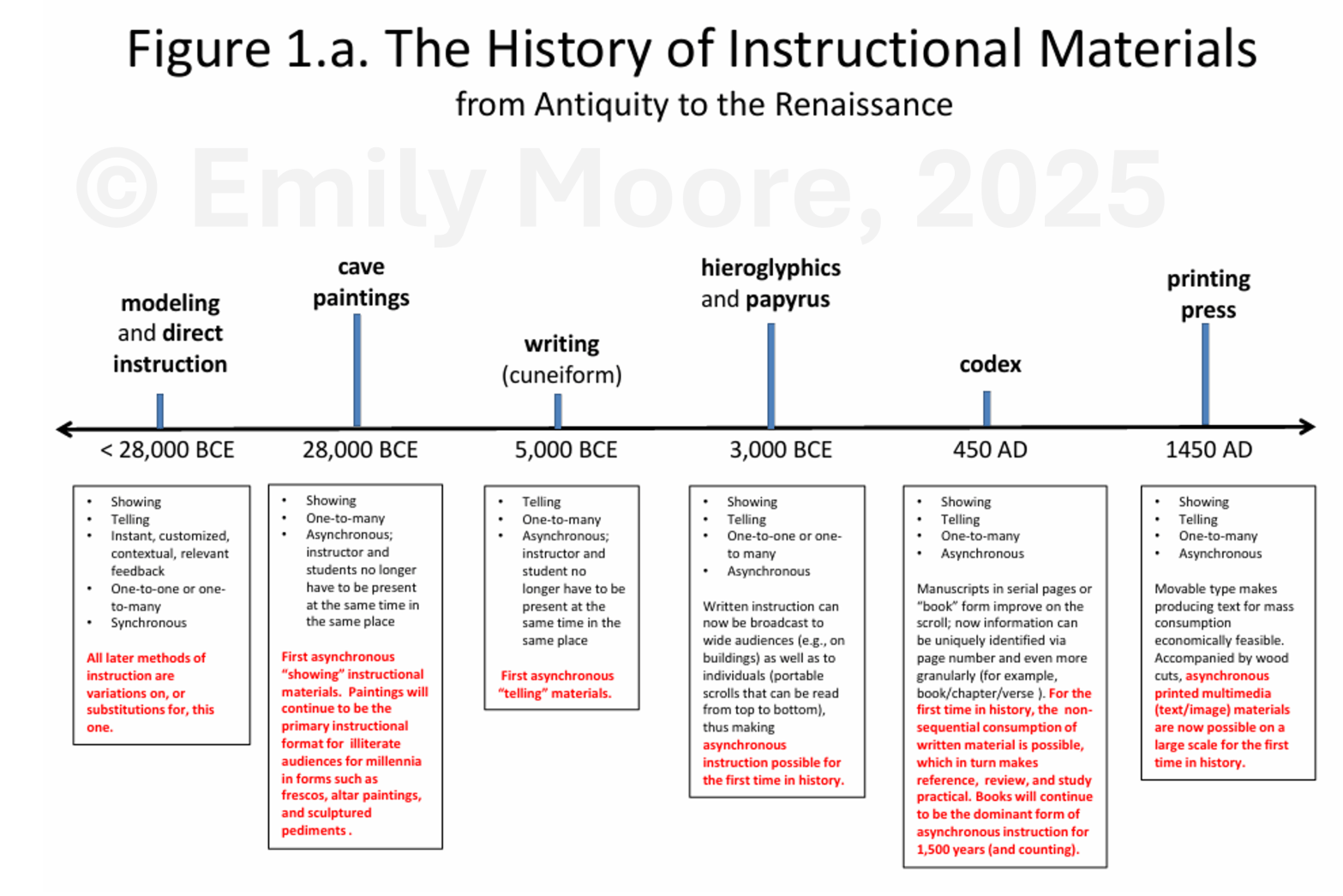

Instruction is nothing more or less than a specialized form of communication. So it shouldn’t come as a big surprise that over the millennia, each time a newly invented communication technology became widespread, it was almost immediately leveraged in education and training.

Knowing what’s been tried, what’s failed, what’s succeeded universally, and what’s succeeded in niche scenarios is extremely valuable. It allows us to stand on the shoulders of generations of both instructors and materials creators; to avoid some of the mistakes and dead-ends they experienced; and to benefit from the effective strategies they devised and described.

To do this, however, may require us to expand our definitions of instruction—to step back and see the common elements in, say, e-learning and thousand-year-old apprenticeship scenarios.

Prehistory: Modeling, direct instruction, apprenticeship, and games

Instructional elements from this era that we can apply today:

- Visual, customized face-to-face demonstrations accompanied by real-time explanations.

- Personality-driven instruction.

- Instructor-to-learner and learner-to-learner interactions and relationships.

- Authentic assessments characterized by high stakes, nuanced, real-time feedback.

- The building of formative skills (such as logic) through low-stakes play/competition.

Middle Ages: Codex

Instructional elements from this era that we can apply today:

- Asynchronous learning (only available for literate audiences able to access materials).

- Information architecture that results in an organization of text presented, unlike the continuous presentation restriction of a parchment scroll, in a form that enables quick lookup of specific information (e.g., uniquely identified page number, sections, and key words).

- Thoughtful juxtaposition of text and images.

Mid 1800s: Distance learning (with assessments)

Instructional elements from this era that we can apply today:

- When instructor and learners are separated by time or geography, instructional materials must be as clear, accurate, and concise as possible. (In other words, removing the instructor from the learning triad requires the other two components—learners and materials—to up their game, so to speak.)

- When instructor and learners are separated by time or geography, instructional materials must include self-assessments (questions accompanied by answer keys) and worked examples.

Early 1900s: Instructional films and radio

Instructional elements from this era that we can apply today:

- In asynchronous learning, use real-time movement to engage, motivate, drive empathy, and show real-life interactions and processes.

- In asynchronous learning, use speech (audio) to engage, motivate, communicate aural nuances, and drive close listening.

1980s: Computer-based instruction

Instructional elements from this era that we can apply today:

- Use auto-graded instruction (vs. self-graded assessments) enriched with game strategies (leader board, countdown timer, points) to ease the learner burden and make assessments feel more like games.

- Develop graded and ungraded group activities, including discussions, that work for learners separated by time or geography.

- Replace the face-to-face “administrative” functions that are lost when learners and instructors are separated by time or geography but must interact with each other or with materials frequently (e.g., clearly communicate when to show up, where to locate materials, what activities are due when, how to troubleshoot or whom to contact to resolve hardware/software/connection issues)

The bottom line

The old saw “those that fail to learn from history are doomed to repeat it” was never truer than when applied to instructional design.

When we don’t understand the principles that underlie yesterday’s approaches to instruction, we’re likely to dismiss or belittle them. Then, when the next new “new thing” comes along, we’ll lack the context necessary to evaluate it meaningfully. In other words, without knowing what has worked historically for education and training and why, we’re left with only two courses of action: reject future technologies, or uncritically embrace them.

And neither of those extreme approaches, historically speaking, tends to end well.

What’s YOUR take?

Were you surprised by the appearance of any of the technologies on either of the two timelines presented in this article? What “new” capabilities, if any, do you believe recent innovations (such as AI) offer for instruction? Please considering sharing your thoughts in the comment box below.

Leave a comment