Note: Dear friends, this post is early! It shouldn’t have been posted until September 8… but I’ve found WordPress’s ability to schedule posts problematic, and I won’t have to access to a device on September 8–so I’m posting this piece nearly a week in advance. The next issue of Moore Thinking will appear on September 15, back on schedule.

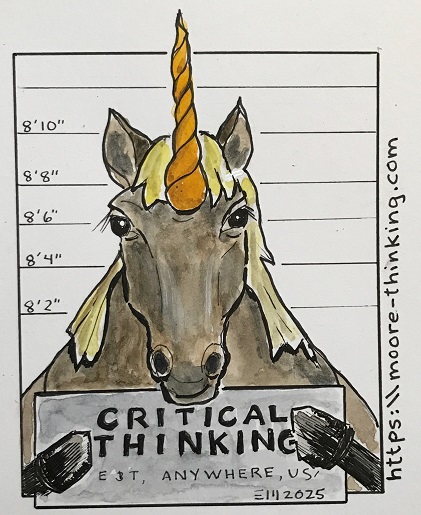

Critical thinking is the elusive unicorn of the education and training space: everyone talks about it and most of us feel sure we would recognize it if we saw it in the wild—but few of us understand what it is, how it develops, why it seems to be so scarce, or what we can do to help nurture it.

What exactly is critical thinking?

Critical thinking (or, as it was known a couple of generations ago, thinking) refers to the ability to go beyond memorized facts and concepts to form connections, generate insights, extend, extrapolate, contextualize, and predict. In the simplest terms, people who think critically go beyond who, what, when, and where to consider how and why in meaningful ways to drive useful, valuable, real-world results.

What does critical thinking look like?

In education, critical thinking takes the form of students who can apply knowledge and skills not just to a given subject, but across the curriculum and outside the classroom. Examples include students who:

- Apply the composition skills they learned in English to the writing of an essay assigned by their Biology teacher;

- Apply the knowledge they learned in Physics to their Drivers Ed course; and

- Apply the formulas and computational skills they learned in Math and Statistics to comparison shop and pay for a college.

In training, critical thinking takes the form of employees who can not only perform a process, but also handle disruptions that occur during its performance, troubleshoot the process, improve it, and even replace it if necessary.

How was critical thinking developed historically?

In the western classical tradition, education was divided into three cumulative stages, beginning with the Grammar stage, progressing to the Logic stage, and ending (for most) with the Rhetoric stage. These three stages were referred to collectively as the trivium. The purpose of the trivium, perhaps not surprisingly, was to produce students capable of thinking critically.

- Grammar stage. Usually, when we hear the word “grammar” we think of English or some other natural language grammar—we think of structure, syntax, and semantics. And that’s one correct meaning. But “grammar” in this context means something else: it refers to the elementary principles of a given field of knowledge. In the grammar stage of the trivium, the goal is for students to gobble as many nuts-and-bolts facts and concepts about as many different fields and disciplines as possible, from geography to geology, biology to poetry, language to history, medicine to horticulture, and everything in between. The ability to think critically requires a broad base of accurate knowledge spanning multiple subjects.

- Logic stage. In this second stage of the trivium, the goal is to help students begin to connect all the facts and concepts in all those disparate subjects that they absorbed during the Grammar stage. They learn to relate facts and concepts by contextualizing and differentiating topics and subjects; comparing and contrasting them; abstracting them; and noting similarities and dissimilarities among them. The ability to think critically requires an understanding of how facts and concepts within a subject and among subjects relate to each other.

- Rhetoric stage. In the final state of the trivium, students practice putting together everything they learned in the first two stages to make meaning. Not to identify the meaning other people have ascribed to a given question or problem; but to determine what they, the students, think; why they think it (what evidence they’ve found to support their assertions); and to be able to express their assertions in appropriate, contextually relevant ways that include expressing their ideas effectively, taking independent action, or persuading others to take action. The ability to think critically is the ability to determine the best course of action based on reason and evidence, and to take that action.

What classical strategies can we apply today?

Few U.S. schools adhere to the trivium these days. But even in the absence of a cohesive, integrated curriculum, there are several strategies we can apply to our next instructional project to support the development of critical thinking here and now, meeting our learners where they are today.

- Grammar. We can provide as much accurate information about as many relevant, meaningful, real-world topics as possible and present it in as clear, concise, and complete a format as we’re able. The broader the base of knowledge we provide our learners, the more patterns and connections learners will be able to draw from later.

- Logic. We can help our learners differentiate, group, contextualize, and form connections among topics by:

- Pointing out similarities and dissimilarities to help learners group and differentiate facts, concepts, and skills;

- Using analogies, metaphors, and similes to help learners activate prior knowledge and make memorable connections between concepts they’re familiar with, and concepts that are new to them;

- Presenting topics not as discrete, disconnected disciplines but as living components of a larger, real-world context to help learners understand relationships and make meaning;

- Describe how processes and tasks were performed—and concepts understood— historically, and how they’re performed/understood contemporaneously in other parts of the world to help learners connect alternatives to different goals, different requirements, different consequences, and different sets of restrictions—all of which drives learners’ ability to extrapolate, predict, troubleshoot, and innovate.

3. Rhetoric. We can help our learners feel confident about researching, analyzing, making meaning, and actively expressing their assertions by teaching and modeling these skills. And we can make it a point to describe the historical development of concepts and processes to help learners develop confidence in themselves by internalizing the necessity of effort, attempts, failures, refinements, and repetition to eventual success.

The bottom line

Critical thinking isn’t “one poke, one jump.” It can’t be developed overnight or replaced by a chatbot. The ability to think critically depends on acquiring an extensive range of accurate, real-world facts; making meaningful connections among all those facts; and leveraging those connections to drive actionable conclusions.

Fortunately, we don’t have to travel back in time or reinvent education to help support and drive critical thinking skills in our learners (and ourselves). We can apply the strategies in this article today, one at a time.

And who knows? If enough of us do, someday soon that elusive unicorn might become as common and familiar as a garden-variety horse.

What’s YOUR take?

Do you consider ways to support critical thinking in the instructional materials you produce? What strategies or approaches do you apply—and how do you assess their impact? Please consider leaving a comment and sharing your hard-won experience with the learning community.

Leave a comment