If you’re in any online communication field—including education, training, and web design—you’ve likely heard the terms ADA compliance, 508 compliance, and accessibility.

But what do these terms actually mean? Are they synonyms? Requirements, or merely suggestions? Do they apply to your project? Should you be doing something about them?

Like so much of the direction around web-based usability conventions, these topics aren’t clearly articulated or disseminated, so rumors and disinformation (“Accessibility? Just add an ALT tag to images!”) abound.

Here’s the least you need to know about why and how to make your online materials accessible.

What are ADA, 508, and accessibility?

Two separate pieces of U.S legislation—The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) and Section 508 of The Rehabilitation Act of 1973—require U.S. government agencies, as well as businesses and non-profits that serve the U.S. public, to follow specific guidelines around communications.

The goal of these governmental guidelines is to ensue that the online information people need is accessible to them; that is, to ensure that people who have physical disabilities or deficits, such as hearing or vision deficits, have access to public-facing information that’s comparable to the access that people without these disabilities enjoy.

The implications of this legislation extend to all forms of communication, not just web-based communication (and not just communication in text form). But for the purposes of this blog—which is to help you, dear reader, improve the online communications you create—the most relevant guidelines are the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines or WCAG (version 2.1 as of the time of this writing).

Who needs to conform to these accessibility guidelines?

While only U.S. government agencies and businesses/non-profits that serve the public are legally required to ensure their web content follows the WCAG, it’s a good idea for all of us to consider applying as many of the WCAG as we can to any content we plan to deliver online for two reasons:

- Applying many of these common-sense guidelines actually results in stronger, better-designed materials that serve all audiences more effectively.

- Applying the remaining guidelines (the ones that make or break accessibility for audiences with visual and hearing impairments) increases our potential audience.

Where’s the exhaustive accessibility “what to do” and “how to do it” list?

The WCAG lists specific steps we can take to make the instructional content we deliver online conform to Section 508 requirements and to be as accessible to as many people as possible. Unfortunately, it can be a little tough to find.

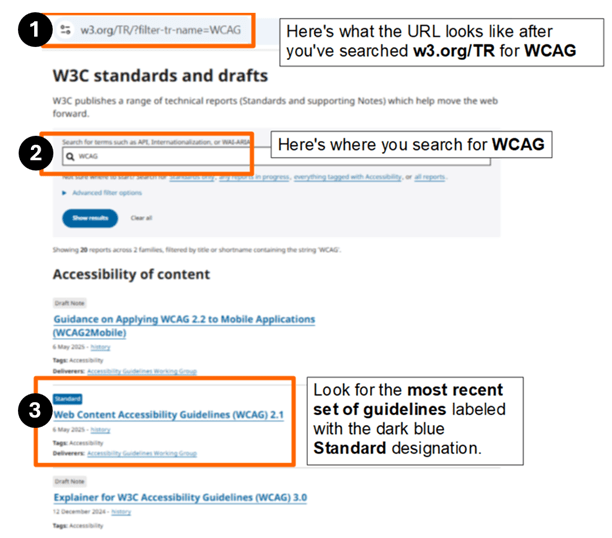

To access the latest version of the web content accessibility guidelines (see Figure 2 below):

- Pull up https://www.w3.org/TR/

- Search for the term “WCAG”.

- Scroll down to see the most recent list labeled standard. (Lists labeled “draft,” as you might expect, are still works in progress.)

Example guidelines culled from the WCAG 2.1 Quick Reference

This baker’s dozen of accessibility guidelines will give you an idea of the kinds of strategies required to meet Section 508 guidelines. Note that applying the following guidelines will improve your materials for all audiences, not just audiences with special needs.

- Organize all content in the flattest possible hierarchy—preferably no more than one click deep. Imagine audiences who rely on screen readers trying to make sense of web copy that descends from one click to another to another and then backs out, click by click, to the original document. The task is nearly impossible. Minimizing the overall number of links (and restricting links to a single layer) minimizes audience confusion. It helps all audiences find what they need, and make sense of what they find, quicker and easier.

- Provide all required materials in static form that can be read online in the form of web copy, closed captions, or downloadable files (such as text transcripts or PDF files). Following this guideline allows audiences with hearing impairments to consume all text by reading, and audiences with sight impairments to consume them by using a screen reader. It also supports literate audiences who prefer text because it’s much quicker for them to consume than audio.

- Present text sequentially and group it meaningfully. Ensuring that all text reads from left to right and from top to bottom, and that all text is presented in labeled lists and titled paragraphs, allows audiences who must rely on screen readers to make meaning. Avoid using non-sequential layout schemes such as tables, which present difficulties for audiences who must rely on screen readers.

- Present text that clearly contrasts with the background (black sans serif text on a white background is best) to support audiences with visual limitations and to help all audiences read quicker.

- Don’t rely on color for meaning. Because screen readers (and some audiences) can’t differentiate between colors, any colors you use (such as green and red) must be accompanied by text (such as the words Start and Stop).

- Either don’t include background music at all, or provide audiences a way to turn the background music off. Doing so supports all audiences, but especially those with hearing or cognitive processing issues.

- Don’t substitute images of text for actual text. Screen readers can’t read text, such as callout text, that has been flattened into an image.

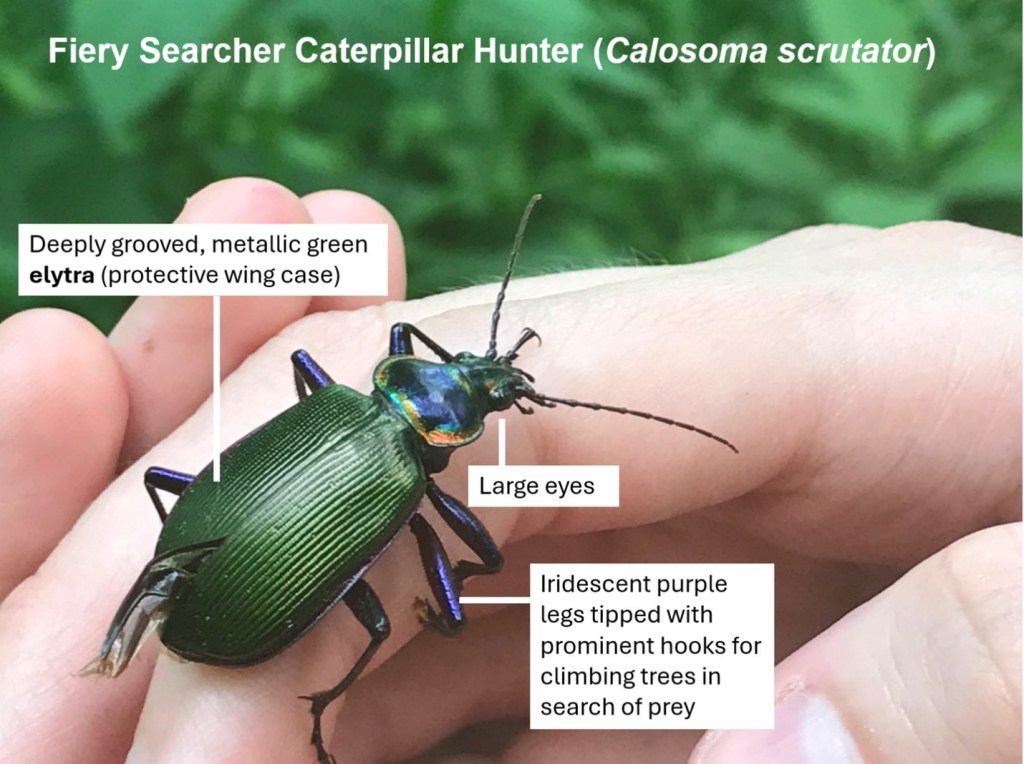

- When including static images into a web page (which is accomplished using the HTML IMG tag), use the IMG tag’s ALT attribute to describe to audiences who can’t see the image—either because they have vision issues, or because the image didn’t load for some technical reason—what the image is, and what’s important and relevant about the image. See Figure 3 below for an example.

- Don’t include blinking objects onscreen, which can trigger seizures in some audiences (and are rarely, if ever, relevant to instruction in any case).

- Ensure links are labeled accurately. All link labels should describe accurately what audiences can expect if they decide to click the link.

- Ensure navigation is consistent. All navigation options should be labeled consistently (e.g., NEXT and PREV), appear in the same place onscreen (e.g., bottom right of each screen), and behave the same way (advance or back up exactly one screen).

- Make all interactivities accessible via keyboard. Drag-and-drop and hotspot activities are difficult or impossible for audiences unable to see well or to use a mouse, so offer multiple-choice, fill-in-the-blank, or other assessment types instead.

- Don’t assign discussion boards. The deeply nested hierarchies of discussion boards are difficult to make sense of when read sequentially, especially since few discussion posts explicitly reference either the post to which they’re responding, or the original prompt.

How difficult (expensive) is it to make online materials accessible?

There are quite a few WCA guidelines, and applying them all can be a significant undertaking. For big projects, it might make sense to hire a professional accessibility expert to apply them all quickly, confidently, and consistently (vs. requiring each of our developers to get up to speed independently).

The best way to approach the decision on how accessible to make our materials is to focus on value—to our audiences, and to the ultimate success of our instruction—rather than cost, and to realize that the effort we put into accessibility is an investment that pays off not just immediately, but over the life of our materials.

What’s YOUR take?

How does your team approach ADA compliance? Do you rely on the label-in-the-ALT-attribute approach? Are there specific sections of the WCA guidelines that you always (or never) implement? Why? Please consider leaving a comment and sharing your hard-won experience with the learning community.

Leave a comment