Publishing anything on the web—from web copy for an e-commerce site to downloadable documents, e-books, explainer videos, online repositories, and asynchronous education and training courses—implies potential consumption by international audiences.

And international audiences come to our materials with different needs and different expectations.

There are several things we authors, UX/UI experts, and instructional designers can do to prepare for localization (if that’s planned for our project) and, at the same time, to support international audiences in addition to native audiences who also happen to be novice learners.

That’s a win-win-win, all for the cost of applying the following simple strategies!

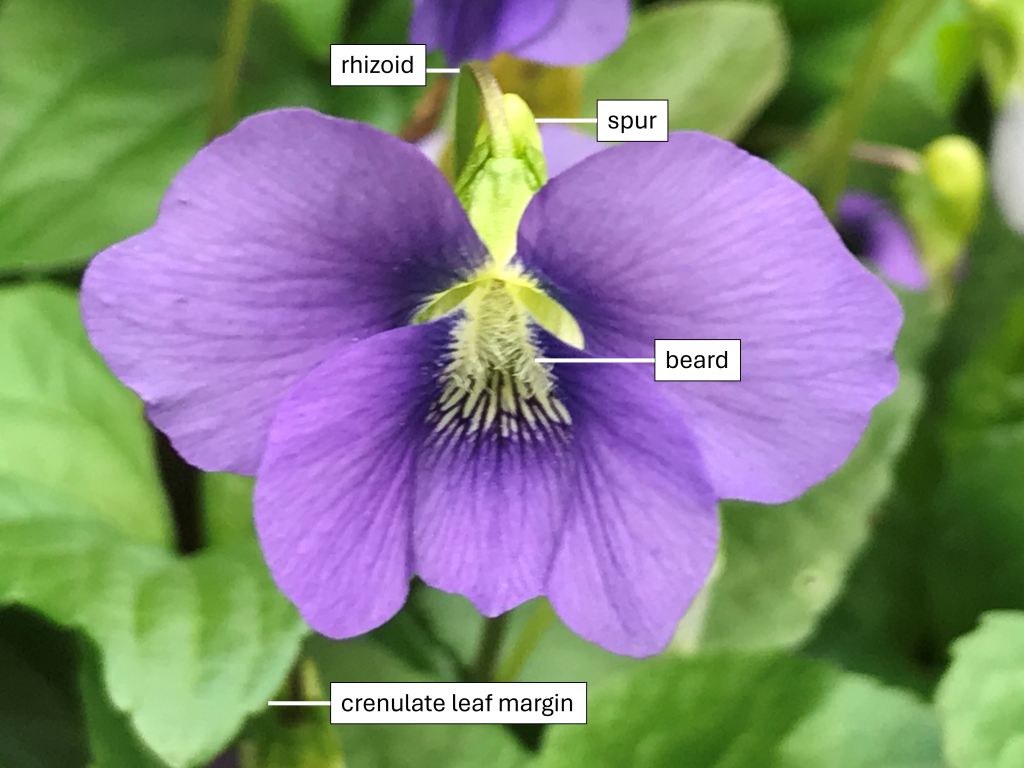

1. Decouple annotations from images using numbers. Positioning titles, subtitles, and text callouts over instructional images is extremely effective in most situations because it guides audiences effortlessly to what we want them to notice at point of need.

Unfortunately, adding these explanatory elements by flattening text onto the images themselves dramatically increases the time, effort, and money required to localize our materials for international audiences.

So instead of adding callout text directly to an image (Figure 1 below), add callout numbers and then follow each image with numbered labels, as shown in Figure 2 below. While breaking the contiguity, or nearness, of an image to the text that explains and describes it is not ideal from an instructional perspective, this approach does preserve a good deal of the usefulness of on-image text while simultaneously minimizing localization expenses.

1 = rhizoid

2 = spur

3 = beard

4 = crenulate leaf margin

2. Avoid euphemisms, slang, and idioms. Any term that isn’t standard English—in other words, any term that doesn’t appear in a standard dictionary unaccompanied by the label euphemism, slang, or idiom—will prevent an audience unfamiliar with the term from making meaning. Non-standard terms date our materials and run the risk of offending audiences from other cultures and traditions, too. There’s really no good reason to include any of the following in instruction which could potentially be targeted for international distribution.

Euphemism

A euphemism is a soft, roundabout substitute for a strong or harsh word. Examples of euphemisms include “expire” (for “die”), “economically disadvantaged” (for “poor”), and “issue” (for “problem”). Euphemisms are much more likely to cause misunderstandings in translation than are clear, unambiguous words.

Slang

A slang term is a term in current use among one or more small groups of people that hasn’t been around long enough, or gained enough traction, to appear in a standard dictionary. Most slang terms are in vogue for only a short time and typically don’t translate to other languages. Examples of slang include “bounce” (meaning to end a call or to leave a gathering), “deets” (meaning details), and “sick” (meaning good or desirable).

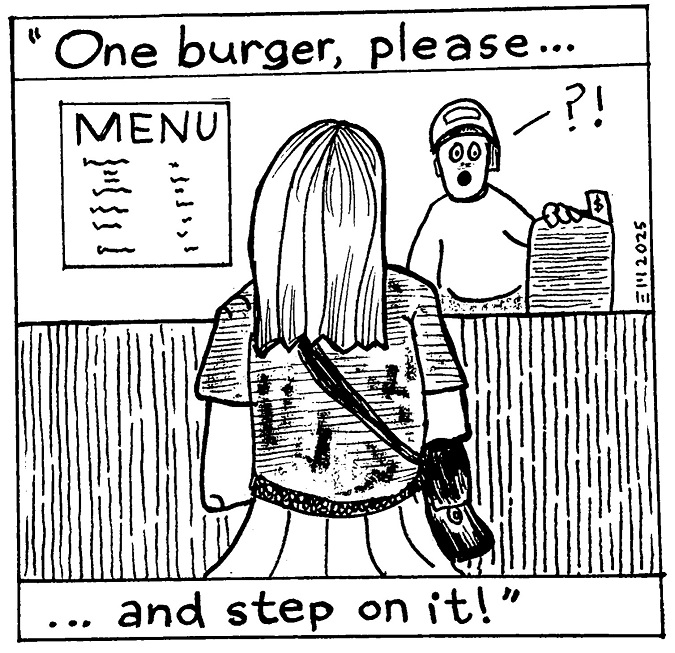

Idiom

An idiom is a word or phrase that can’t be translated literally, but that means something specific—to people who live in a specific geographical area. The term “rubber,” for example, refers to an eraser in British English and to condom in American English, so using this term internationally would likely confuse a significant portion of your English-fluent audience. Other examples of American idioms to avoid in instructional materials are “step on it” (meaning to hurry), “drink the Kool-Aid” (to go along with a crowd to the detriment of oneself or those around one), and “bite the bullet” (to make a sacrifice).

3. Telegraph place and time. You know where your organization is located and what time zone it’s in; but audiences across the world couldn’t possibly know unless you explicitly tell them.

- Incorporate a physical mailing address in a prominent place your audience will see first, such as the top of your home page.

- If you offer synchronous meetings, include either an a.m./p.m. designation (e.g., 5:00 p.m.) or a military time designation (e.g., 17:00) in addition to one of the 24 international time zone designations (such as PST, CST, EST, GMT, and WET).

Pro Tip: Because there are four different time zone designations in the contiguous 48 states alone, consistently adding time zone designations support non-international audiences as well as international courses.

4. Focus on clear instruction (vs. trying to adapt presentations or presentation styles to multiple cultures). The reasons for doing so are practical. For one thing, we can’t possibly know every relevant aspect of every audience member’s culture (especially in situations where audience members register or join our courses at the last moment). For another, few cultural differences are likely to be relevant in the context of our instruction. Instructor sensitivity to cultural nuances is no more and no less important than instructor sensitivity to other audience characteristics, such as their familiarity with a topic or their motivation level.

What’s YOUR take?

Does your team develop instructional materials targeted for international audiences? What tips or tricks have you run across that you’ve found make doing so easier or more effective? Please consider leaving a comment and sharing your hard-won experience with the learning community.

Leave a comment